Anchoring

We tend to rely too heavily on one piece of information, usually the first one, when making a decision or estimating the value of uncertain objects. This initial "anchor" value is used as a mental reference point, which might influence the choice peoples will make.

Studies

Two groups of high school students were asked by Tversky and Kahneman (1974) to compute, within 5 seconds, the product of the numbers one through eight (1 x 2 x 3...) or the reverse (8 x 7 x 6...). Because of the short time, they had to estimate the product after the first multiplications. These first results gave an anchor for their final answer. The median estimate of the first group was 512, while the median for the descending sequence was 2,250. The correct answer is: 40,320.

Judges score better than others on some cognitive illusions like the framing effect (treating economically equivalent gains and losses differently) or representativeness heuristic (ignoring background statistical information in favor of individuating information) but are equally prone to the anchoring effect (Guthrie, Rachlinski & Wistrich, 2001).

Job seekers who anchor first and high in salary negotiations usually get a higher wage. Even a joking comment about an implausible salary could bring the final salary offer up (Thorsteinson, 2011).

Examples

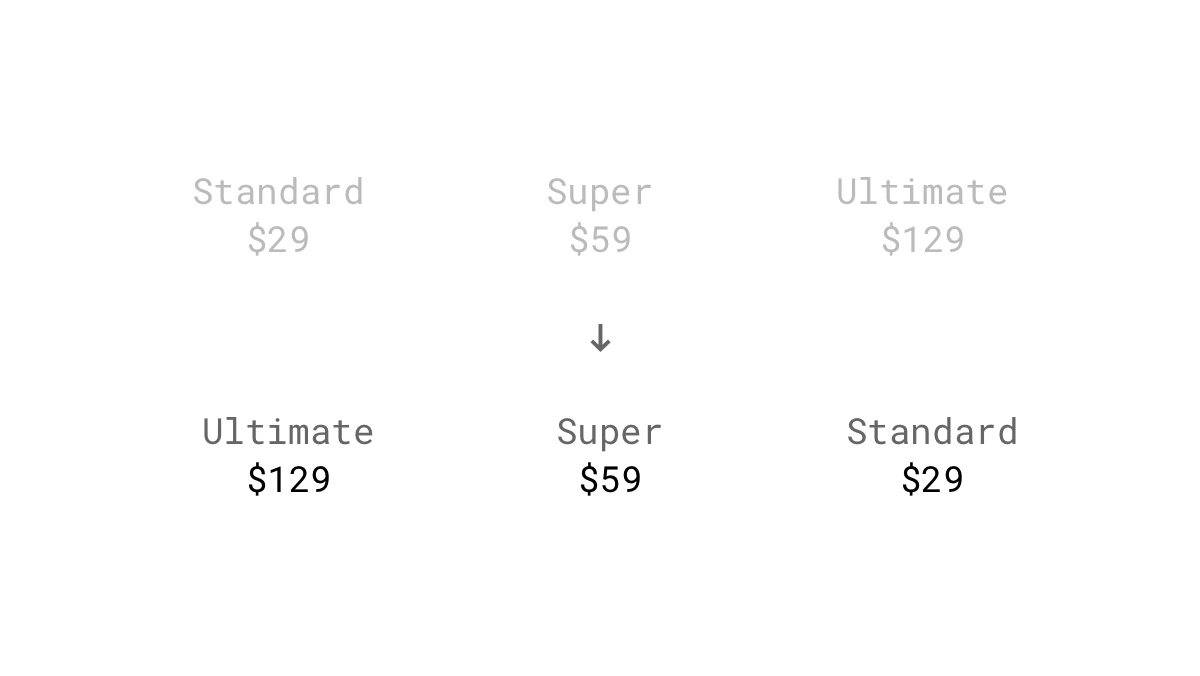

Highest price first

Anchor the price of the most expensive package of your product to the user's mind by listing it first. This order makes the subsequent plan seem like a bargain.

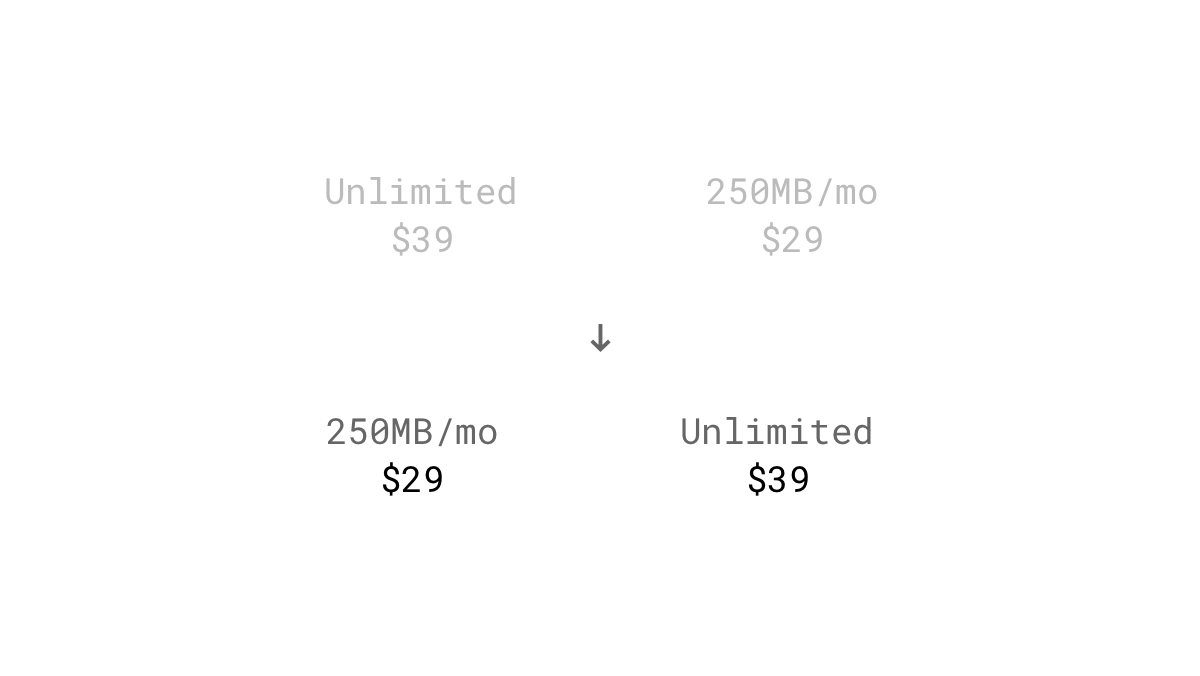

Lower price first

Wait, didn't you just say the opposite? If there is not much of a price difference, try to anchor the lower price. Therefore, the slightly more expensive, but significantly more valuable offer, looks like a steal.

Listing higher-priced unrelated products

A study showed that exposure to higher prices, even for unrelated products can impact people's willingness to pay for goods and services (Nunes & Boatwright, 2004).

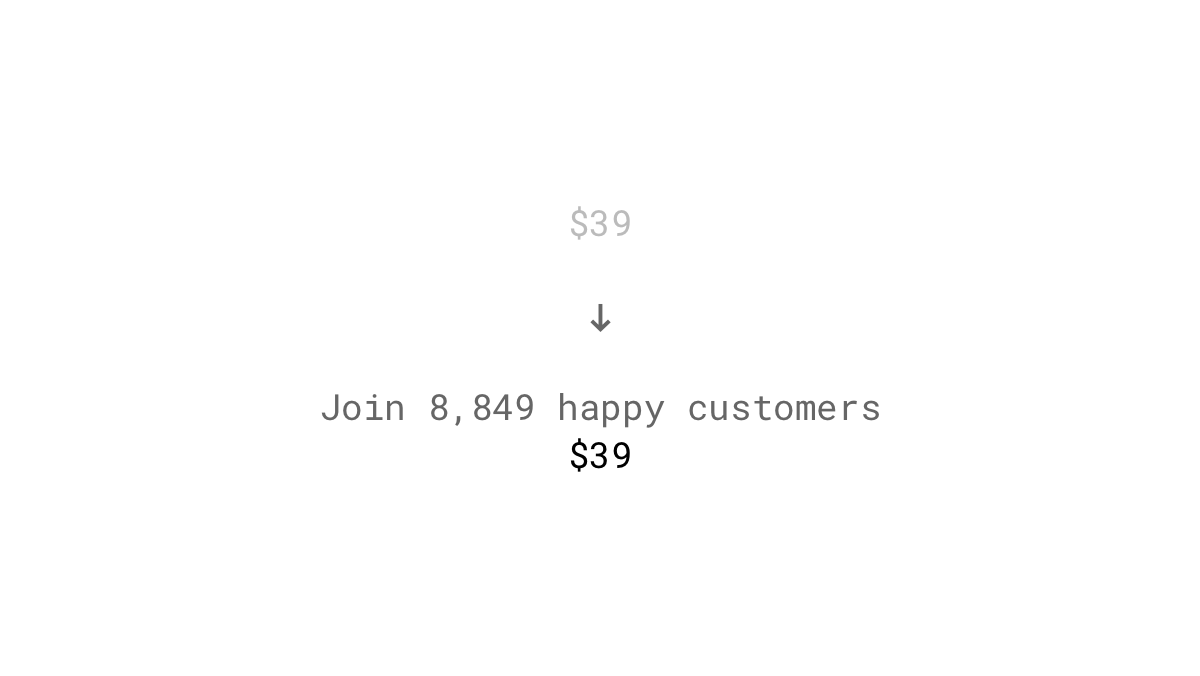

Exposing users to any high number

Anchoring works with any number, regardless of whether that number is a price (Adaval & Monroe, 2002).

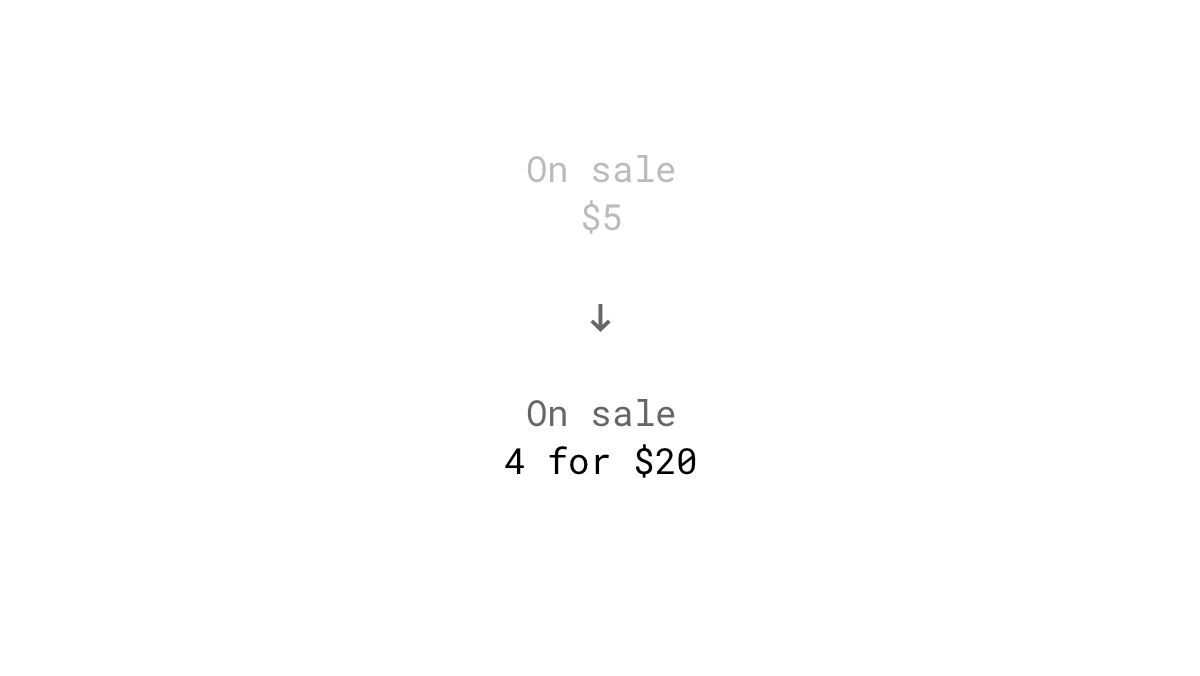

Multiple-unit pricing

The number of units in a promotion serves as an anchor, and indicates which quantity the customer should buy. In an experiment, this tactic increased sales by 32% (Wansink, Kent & Hoch, 1998).

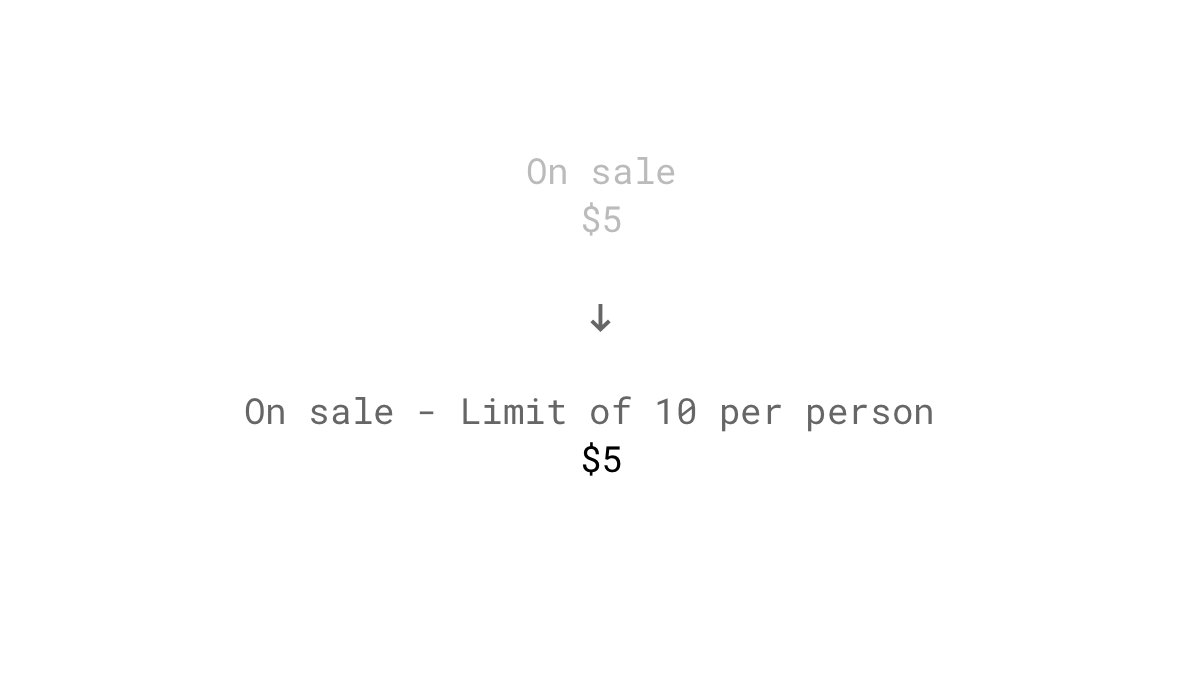

Exposing users to a quantity limit

A study by Wansink, Kent and Hoch (1998) evaluated if setting quantity limits affects shopping behavior. In the experiment, buyers purchased an average of 3.3 cans of soup when they had no limit, whereas shoppers with a limit of 12 bought an average of 7 cans.